Turning an Old Teak Coffee Table Into a Ceiling Lamp

by JavitoBosch in Workshop > Furniture

2671 Views, 44 Favorites, 0 Comments

Turning an Old Teak Coffee Table Into a Ceiling Lamp

Quick summary of what you may encounter if you keep reading:

What am I doing?

I am building a living/dining room ceiling lamp with a used coffee table and other reclaimed materials.

Why am I doing it?

This is a project I had in mind a few years ago. It happens that I managed to find the type of wood I wanted to use a few weeks ago in the form of a coffee table, but I did not really know for what purpose. The funny thing is that I knew I wanted a wooden ceiling lamp but I was not certain about what type of lamp.

How am I doing this?

By forcing myself to turn used furniture into what I want/need. This is a cost-effective, environmentally friendly, sustainable and smart solution. My brain works considerably, but this helps me grow while proving (once more) that I can achieve what I want, the way I want and how I want it to be. I think you should try this too.

Still interested? Watch the video and/or keep reading!

Supplies

I have decided to set a symbolic price for what I am doing. You can get access to the CAD model and the drawings from my shop. This will help me to continue building my future, while inspiring yours. If you think this is not fair, then I suggest you watch the video or continue reading because the design is rather easy and fully documented.

The BoM/BoP file can be accessed from here

Design Requirements

I have a few:

- Replace the current old-fashioned solution.

- Repurpose as much as possible. Only buy what is really needed.

- Since it is a lamp, I want it to have a nice and attractive shape. Let’s say an “artistic” shape (I am not an artist).

- The weight of the lamp cannot be more than 10kg.

- The lamp must fit within a 150x50cm rectangle, keeping a pleasing aspect ratio.

- No further holes are allowed to be drilled in the ceiling order to clamp the lamp. Hence, a suitable fixation method must be incorporated to the design.

- The Centre of Mass [CoM] must be considered in order to avoid any undesired stress within the chosen fixation method. Ideally, the CoM should lay in the middle (balanced).

Concept Design and Modelling Using Fusion360

The idea of triangles…

Initially, I thought of cutting a simple rectangular shape, figure out a fixation method to the junction box in the ceiling and that is it! But, there was something wrong with that idea. I could imagine myself having dinner on the dinning table (functional, it has its purpose), while looking towards the ceiling and thinking “what is that thing?”, “why do I see a reduced-size dinning table stuck to the ceiling?”.

Therefore, I started thinking about textures, shapes and how could I bring all of these to this design. The answer: triangles. I particularly like when a CAD model is meshed and its fully-defined volume is turned into uncountable tiny triangles (aka meshing). These models, if well processed, can be exported and 3D-printed achieving an outstanding, edgy and modern look. Can I achieve this? Yes if I have the patience of spending hours with a set of chisels, carving what I would call a masterpiece. Others prefer the fact of using a CNC machine. However, I don’t have a CNC machine nor the carving skills. Let’s keep thinking, as I need to bring the simplicity and manufacturability to the design.

Why not using wooden triangles embedded in an epoxy panel that is mirror polished? This way the triangles would look somehow suspended very close to the ceiling. This idea sounds nice, but it is a waste of material and what about the mass? It would have been heavy, forcing me to drill holes on the ceiling and its fancy finish.

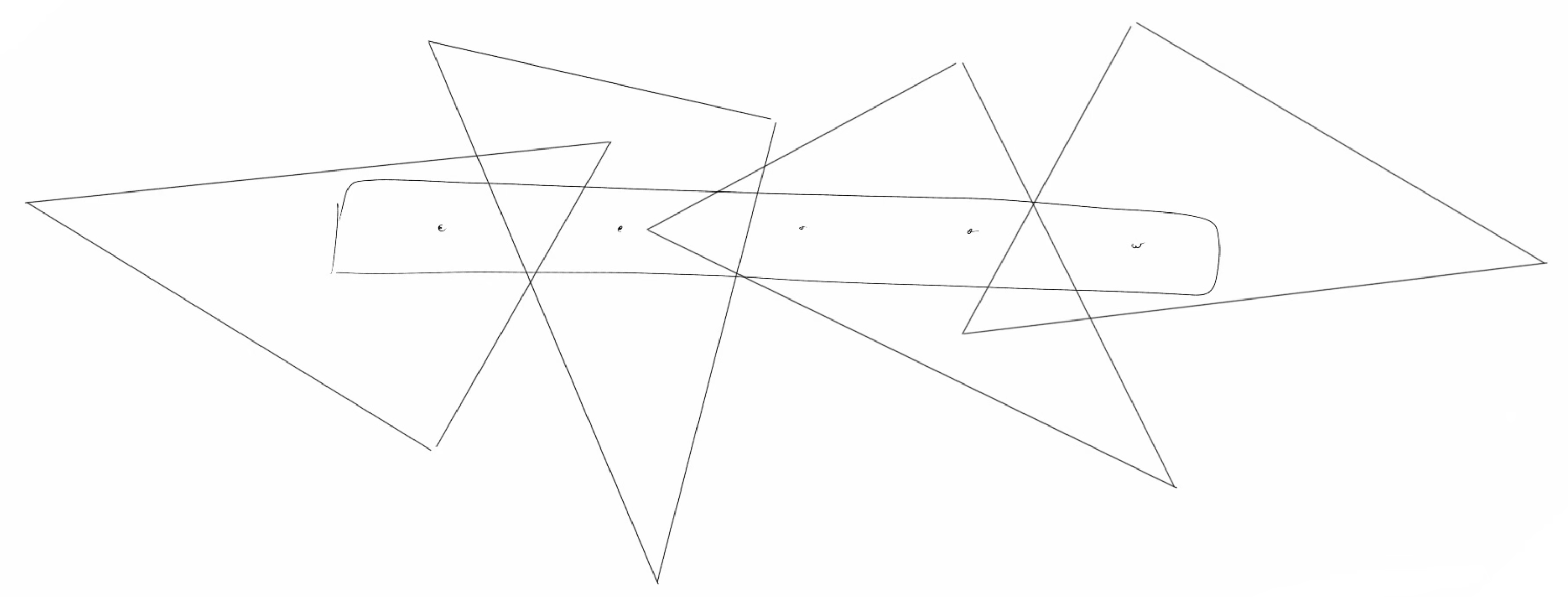

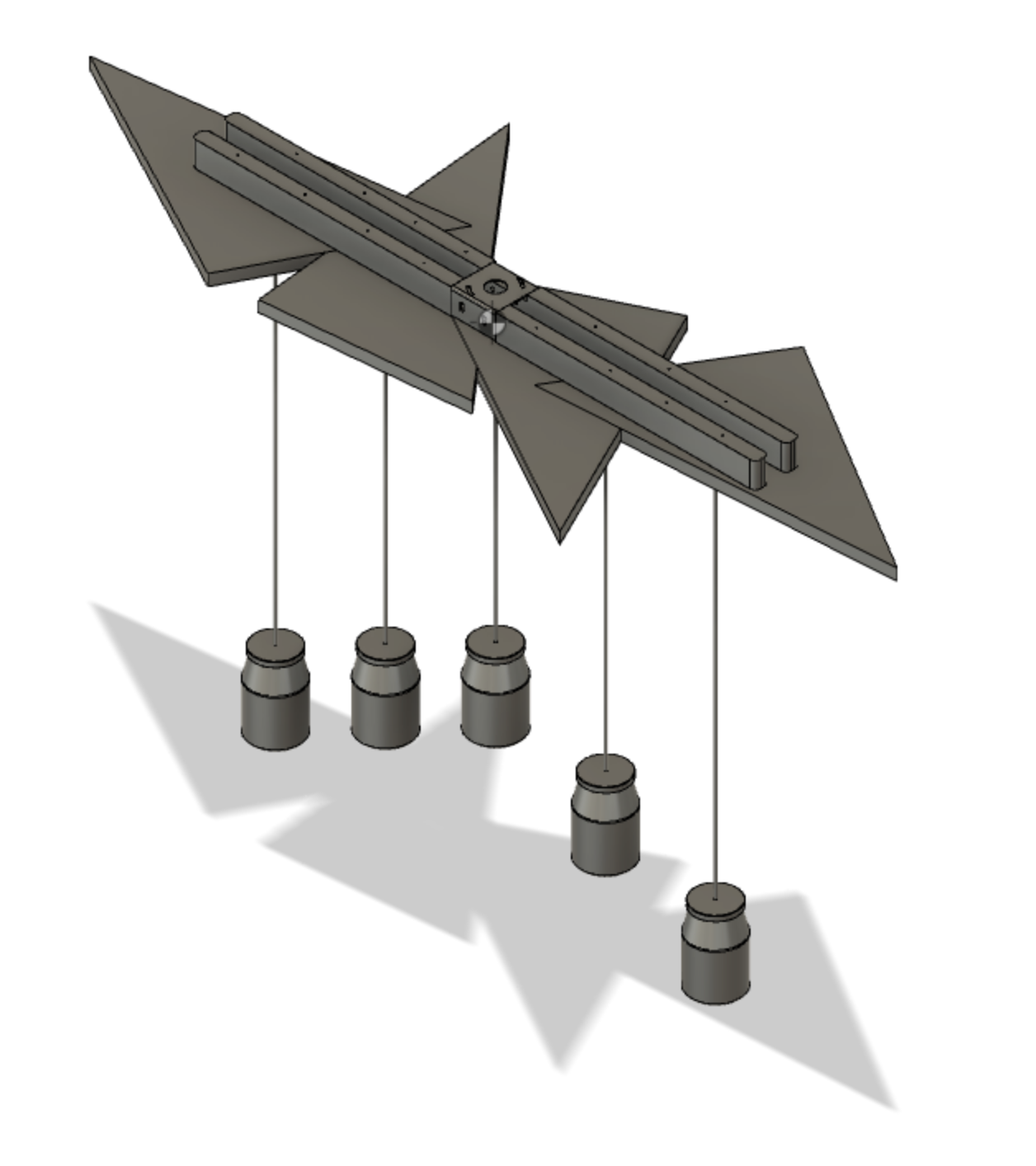

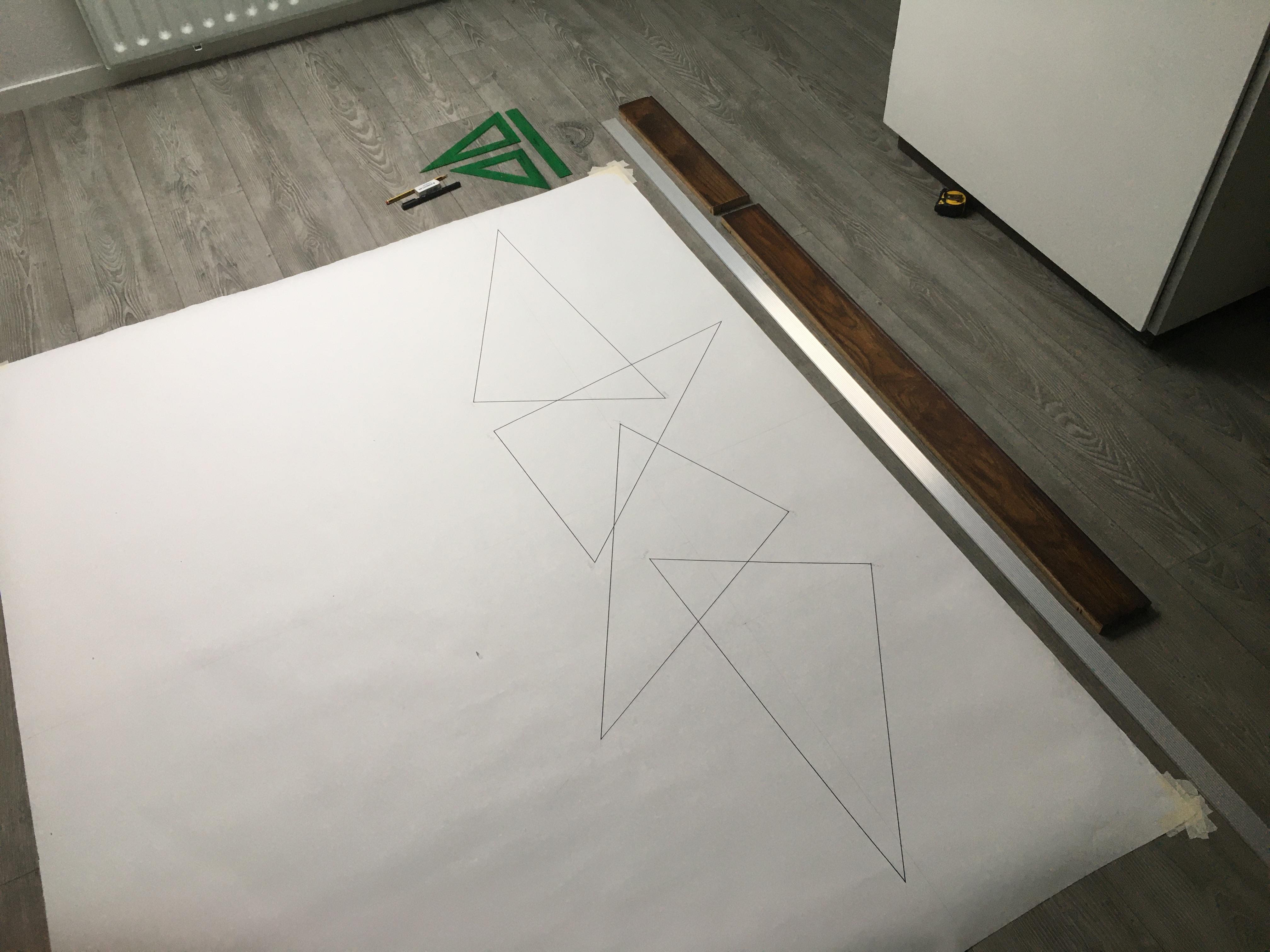

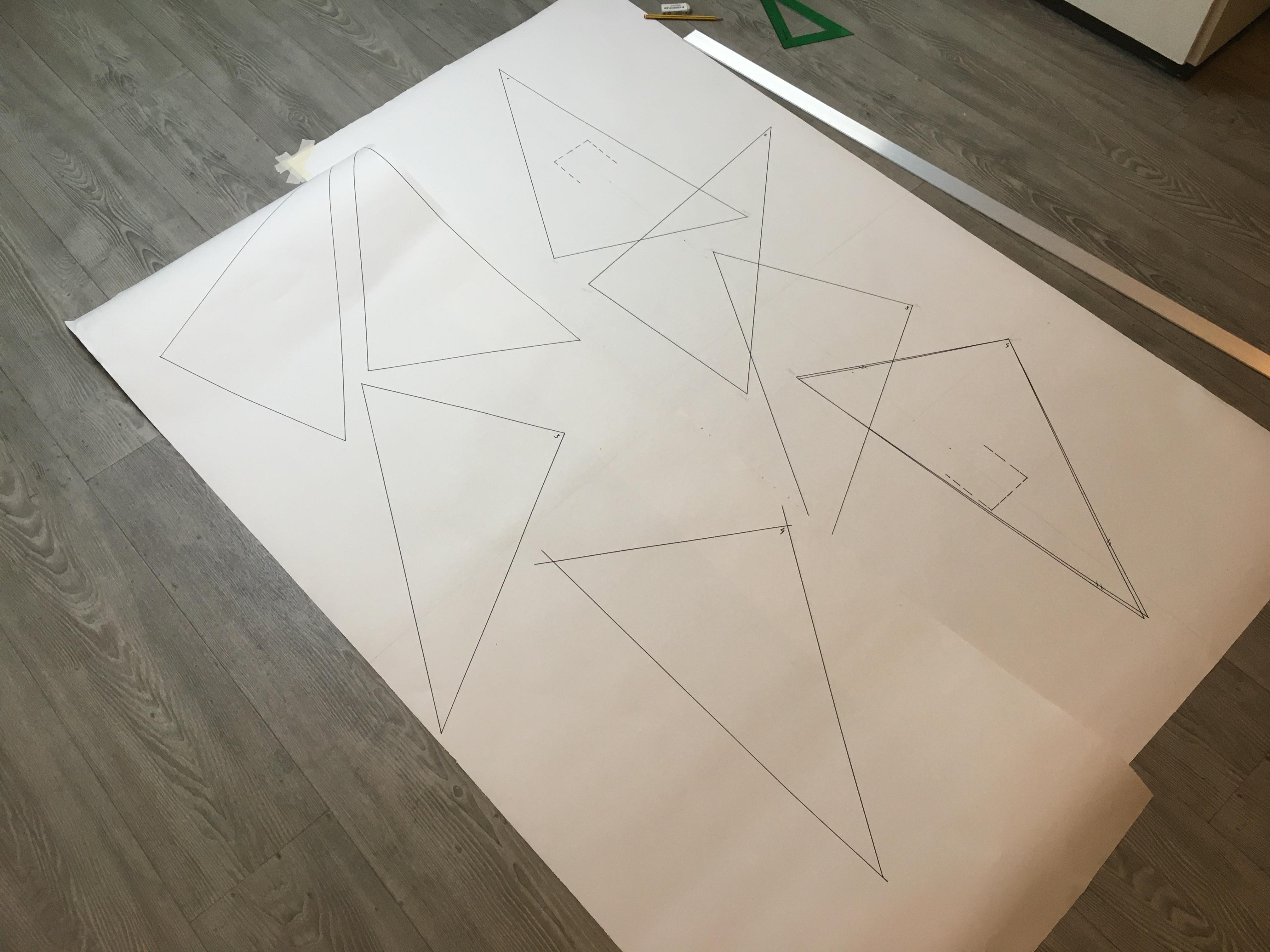

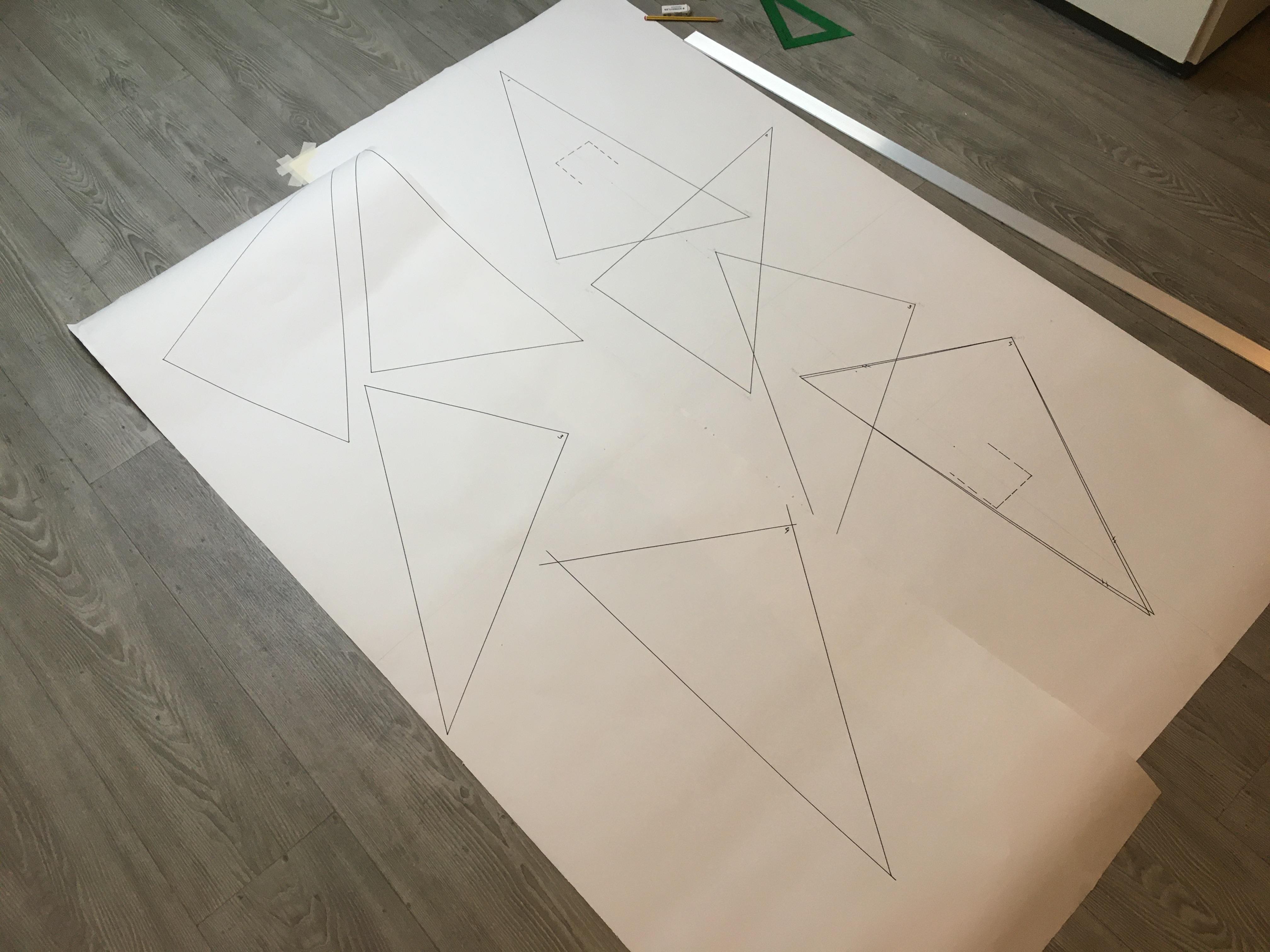

Let’s switch to 2D-triangles. Can we achieve a 3D-effect with a 2D-triangle? My partner suggested overlapping big triangles together in order to achieve the depth. She is good! So I decided to go for big triangles that will be overlapped but eliminating the intersections, resulting in saving some mass. Here I also thought that the direction of the wood grain can make a difference and if the supporting structure was high enough then some deepness could be achieved by how far the triangles are from the ceiling.

From many sketches with overlapping triangles I realised that rotating them (taking advantage of the wood grain) would be very beneficial as I would be able to achieve an irregular shape too. My partner suggested to use the same triangle in order to simplify the design even more. All of the sudden, I felt I almost achieved exactly what I wanted. The CAD model did not take much time.

What if I don’t like triangles?

Well, that is the main asset of this design. The supporting structure is as simple as it gets. The rest is a canvas! You can draw what pleases you the most. As for for the process, I think I just showed you how I managed to get into my “beloved triangular adventure”.

Making the Lamp

How do I manufacture this?

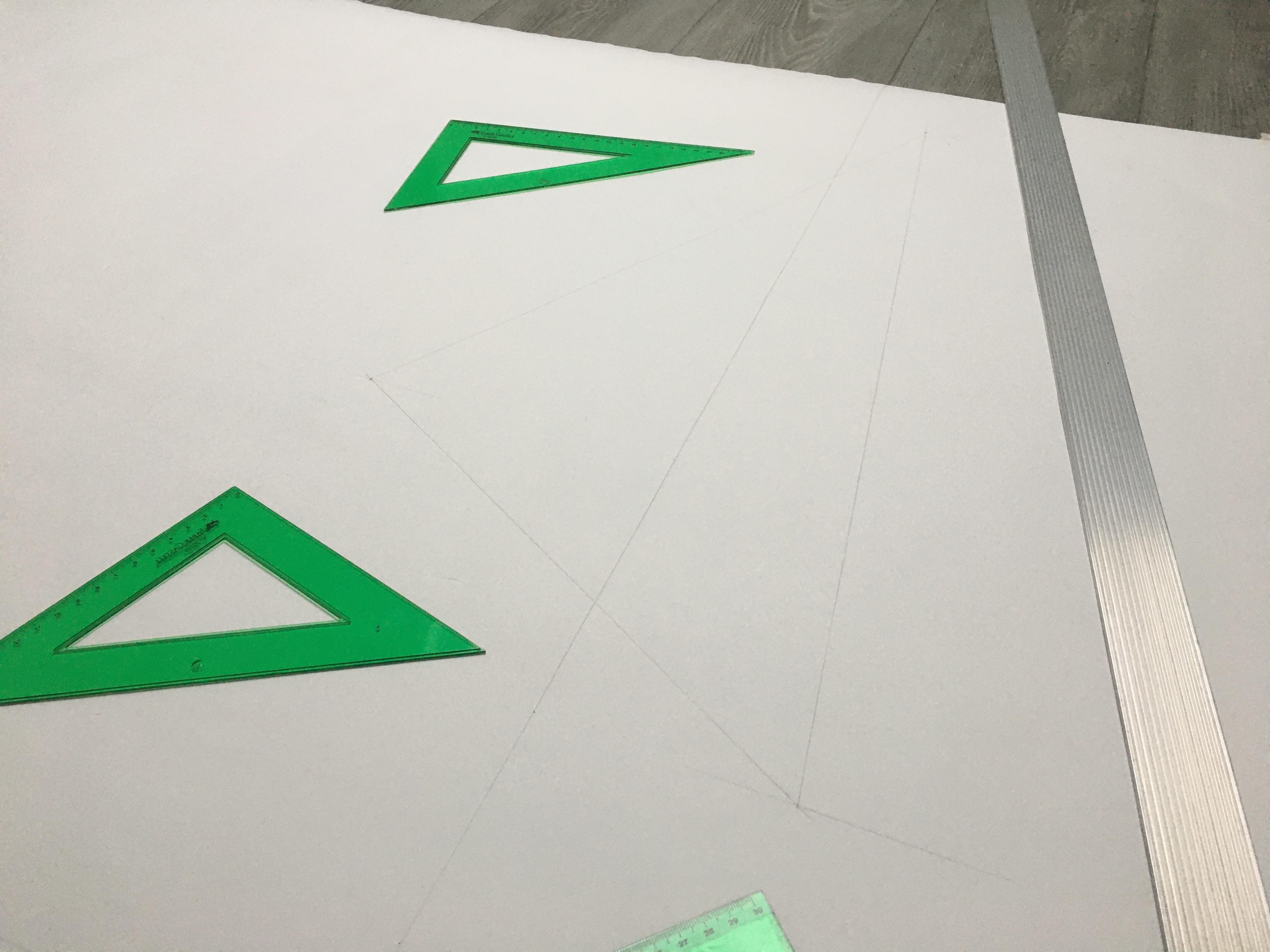

I think it is obvious, but it is a hard question with a simple solution: templates. There are no reference faces that you can really rely on, especially when you are using standard tools. Therefore, why not creating a coordinate system and using it as a reference? It cannot be easier, as this will allow you to draw literally any shape.

Once I have a full-scale model of the triangle mesh, then I can create all individual triangles from the template. There is no need to rely on drawings anymore, just templates. Two sets are needed: one for the whole assembly and the other one for the making of the individual triangles.

I also decided to continue with this approach, since the shape of the lamp itself was merely about design, not functionality. There was no purpose but a nice-looking shape. Therefore, small deviations will not be perceptible.

Triangle mesh

The beauty of this build was achieved with the following steps:

- Draw the shape of the triangles on the wood. Bear in mind which face is going to be visible in the end product and how you can orient the shape so you can also play with the wood grain.

- Cut each triangle to size, trim edges and draw the overlapping features.

- Cut the intersections and proceed with a dry-fit of the triangle mesh. I advice you take your lovely time filing the interfaces and making up for the potential errors you made. The interfacing should look nice as it will be seen if large deviations are allowed.

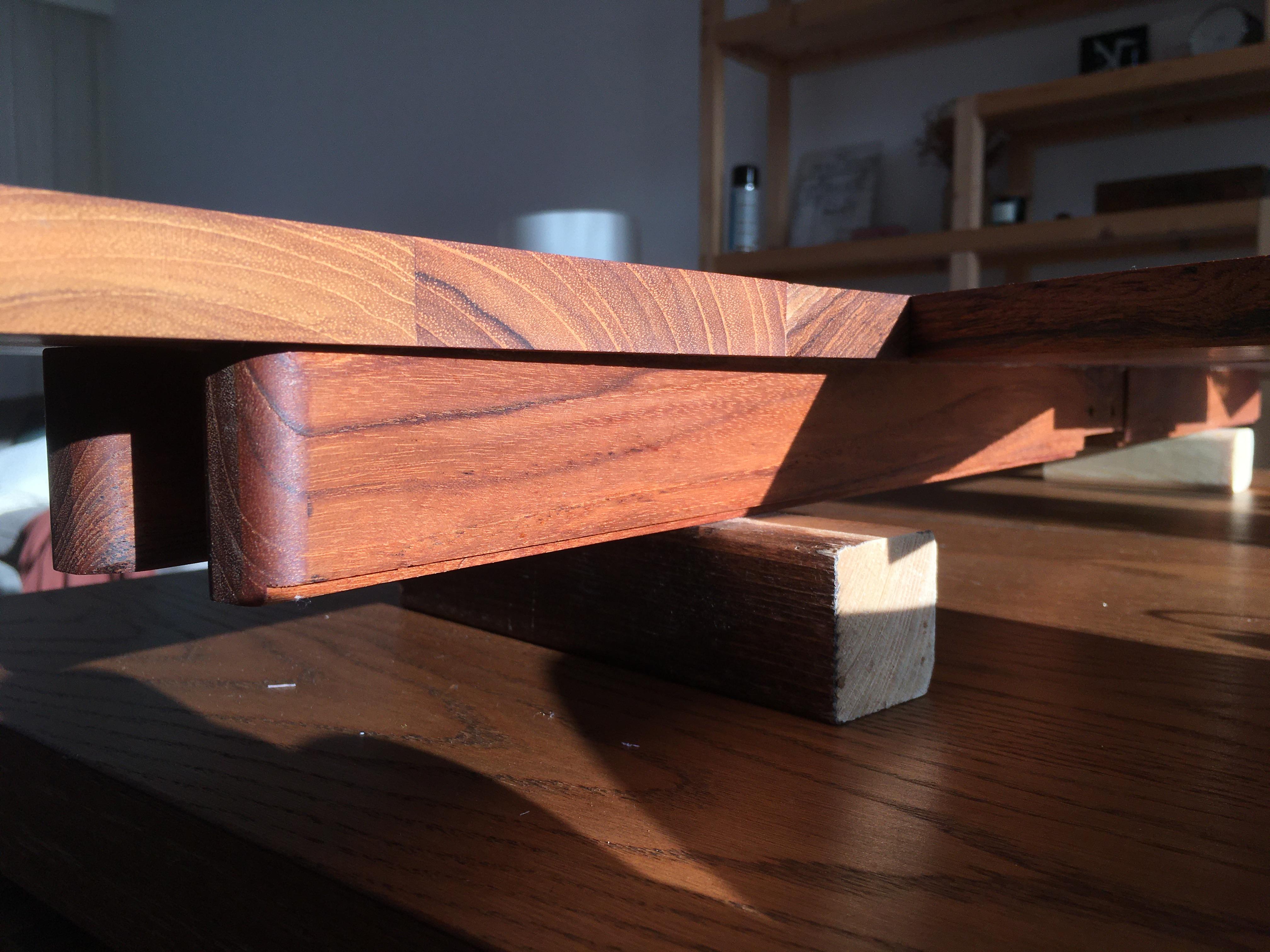

- Time to proceed with the supporting beams that will set a gap between the ceiling and the triangle mesh, serving as structural support for the entire assembly. In my case, I am using the sides of the coffee table. I only needed to cut them to size, round edges and drill holes. Other features like the fixation method to the junction box in the ceiling will be discussed later.

- Give all individual parts a nice sand with up to 240grit.

- I decided to glue all individual triangles and the supporting beams but it is not really needed. The screws that go from the top of the supporting beams are just enough. However, you will need to fix the triangle mesh in place while you drill the holes, keeping everything in place. In my case, I used the support blocks that the coffee table included. They worked just fine. The only downside is that I had to drill holes on my workbench top, but nothing that cannot be fixed. The glue I used is a foamy one, very similar to gorilla glue. I should have used normal water-based wood glue.

- I spent some good time removing all the glue excess and sanding the whole assembly. I had to use 80grit on the visible faces of the assembly because of my glue choice. Something that is true is that the structure felt really stiff.

- Once I was happy with the result, I decided to use a mix of wood dust and water-based wood glue to cover all the imperfections (e.g. holes from the previous build, gaps between triangles, etc). I also covered the surroundings with masking tape to avoid more unnecessary sanding once the paste cures. The result was as expected. Really nice and smart-looking.

- Give it all another sanding session up to 240grit (no need to go finer). Remove the majority of the wood dust remaining with a dry cloth, take the assembly to a different place, clean it again with a damp cloth and wait for it to dry.

- Apply a first layer of the finishing coat of your choice. In my case, wood oil. Once the wood was saturated after ~15min I removed the oil excess with a kitchen cloth, having in mind that all surfaces are very smooth and the chances of leaving particles/bits were really low.

- 24h later I decided to wax the whole assembly. The reason behind is that it protects the wood against moisture, evaporation, odours and grease from the kitchen. The result is so satisfying!

Fixation method to the ceiling

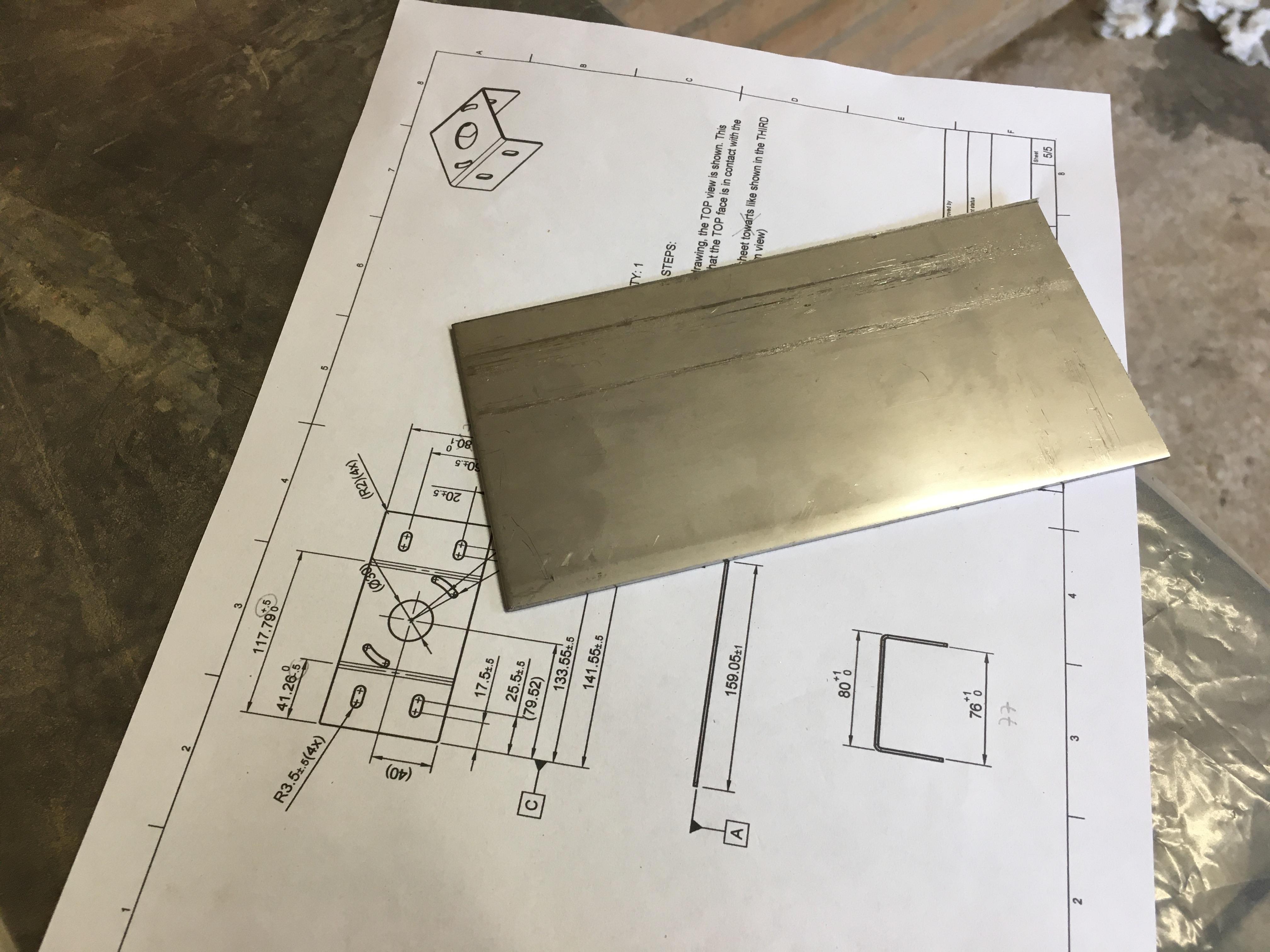

I think I went a bit far by thinking of manufacturing a bracket made of a 2mm stainless steel sheet I had in my garage:

- I had in mind the combination of stainless steel, teak wood and acorn nuts. In my mind it looked amazing. The bracket would have a u-shape and the sides would be exposed. Perhaps in your case this will be different.

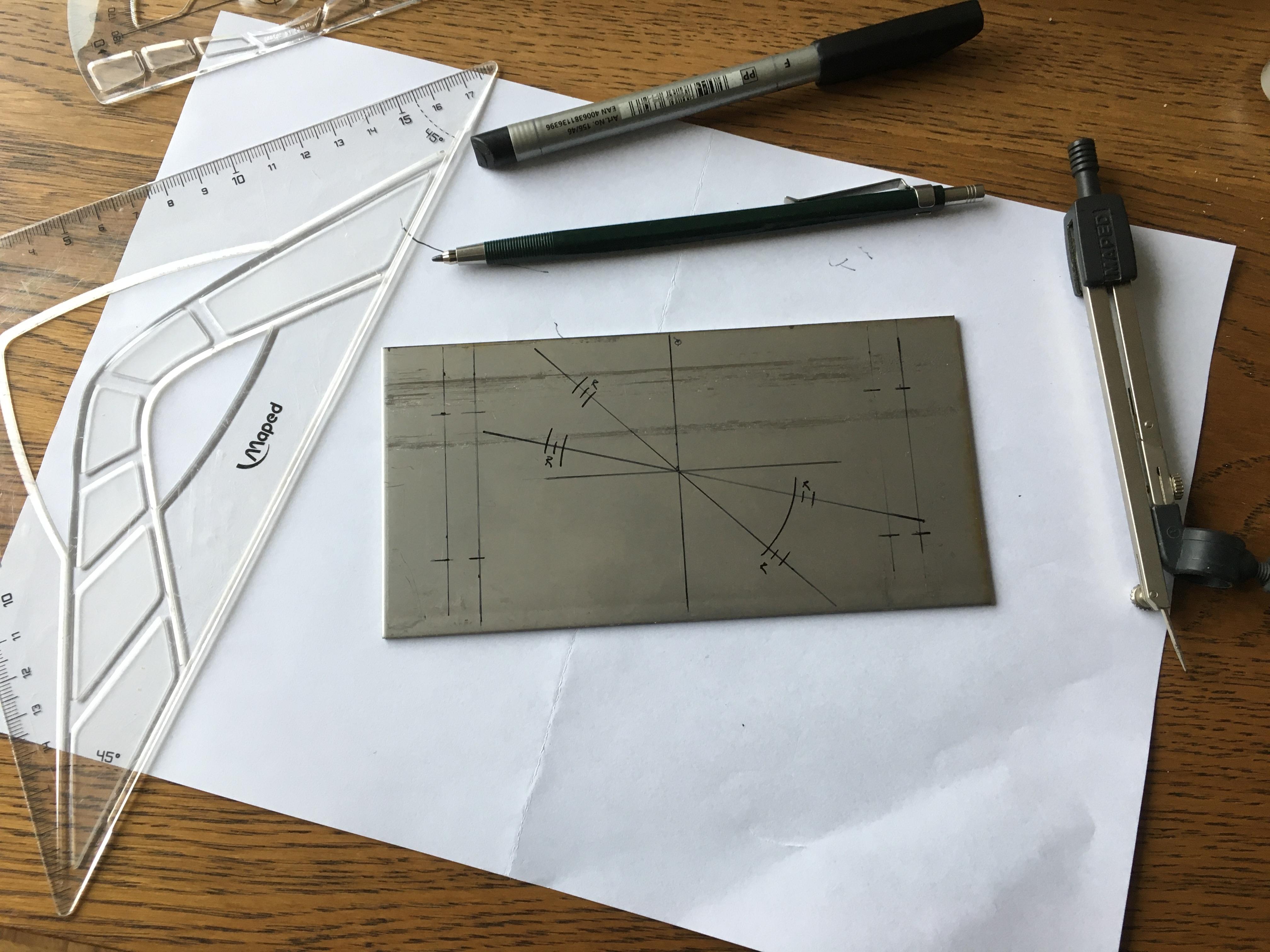

- I spent some time drawing the interfaces in real-scale, so I could verify that it will match the available interfaces in the junction box located on the ceiling. The chance of making mistakes in this case is rather high considering my skills and tools, so I decided to go for slots instead of holes where possible.

- Before cutting anything, measure the interface dimensions of the assembly that is going to be clamped. You may want to change your drawings in order to account for any deviations.

- I do not have specific tools, so for circles larger than 10mm diameter or straight/radial slots I have to drill multiple holes (starting from the sides, so the limits are defined first). The final result can be achieved after a long time hand-by-hand with your favourite set of files and plenty of patience.

- Once happy with the result, it is time to remove sharp edges and round corners. A file should do the job pretty well.

- Bending the 2mm-sheet was a bit of a nightmare with a vice and some wood bits. I ended up hitting the bare steel with a hammer in places I knew they won’t be visible. This is a learned lesson for me. Next time either use 1mm thickness, outsource this task or acquire some appropriate tooling.

- After some time spent on the fine-tuning of the bracket, I decided to go for a brushed surface finish by sanding with a 280grit first and using a Scotch-brite sponge.

- Don’t forget to test-fit the bracket!

Jars

Using jars as part of a lamp is a rather old idea, but still effective from the vintage design point of view:

- Take the jars of your choice and make sure that the bulbs and holders you chose actually fit inside!

- If successful, remove any labels and wash them properly. Most of labels can be removed with warm soapy water. Some others will require the use of kitchen oils, acetone, IPA or even white spirit.

- Take the lids, drill holes for the wires and for ventilation.

- If you are planning to paint the lids, clean them with IPA in order to remove any grease and to activate the surface for the painting part.

- Paint the lids up to your choice. In my case I went for mat black. I think it gives a rustic-posh look. I ended up applying 3 layers.

Final Assembly

Warning: any electrical connection must be made knowing that the networks you are working with are completely off-grid.

This assembly contains three parts: the triangle mesh, the wiring and the jars.

- Be generous with the wiring, so you can comfortably connect it to the junction box.

- I decided to use a black-braided wire for a better look than other available options, and smart LED filament bulbs.

- Fix the wire to the rest of the assembly for safety. I decided to repurpose the same clamping blocks that came with the coffee table by making some additional features and holes in it.

- You can choose to leave all jars at the same height or at different levels. The trick is to do the wiring first, place the lamp in place and decide what length is the most suitable for you. Then cut the wires to size but keep in mind that ~2cm are needed for the bulb holder.

- The braided textile was a bit of a problem because it would struggle to stay in place and it would tear off rather quickly. Using some heat-shrink would work perfectly.

- Place the jar lid first, then the top of the bulb holder (this depends on what kind of holder you have), the connecting elements and the body of the holder. The holder already includes a tab system that clamps the wires, providing the structural support for the jar (and its weight!).

- Finally, screw in the bulb and place the jar.

- Last step is to proceed with a test and to admire the result if no troubleshooting is needed!

Conclusion

I personally loved this project. This has been by far the most artistic thing I have achieved so far. The idea of having all the freedom to make anything you want make is something I would encourage you to experience.

Watching this lamp while having a meal is even better than watching a movie...

See you in the next one!